- Biography

- Milestones

- Quotes

- Photos

- Learn More

Richard Clive Saunders

July 22, 1922-August 20, 1987

Photojournalist |

Photo courtesy Bermuda Sun

| Richard Saunders is one of the few Bermudian photographers to have earned international acclaim and recognition for his work.He spent virtually all of his working life in the United States, establishing himself as a highly respected photojournalist. His work appeared in leading publications such as Life, the New York Times, Paris-Match, Fortune, Look, Ebony and Ladies’ Home Journal and the United States Information Agency’s magazine Topic, which was geared towards African audiences.

Henry Kissinger, Leonard Bernstein, Malcolm X, Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad, author James Baldwin and singers James Brown and Abbey Lincoln were among the famous figures Saunders captured on film. His work is in the permanent collections of the New York Public Library, the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh, the Bermuda Archives and the Bermuda National Gallery.

Fascinated

Born in 1922 to Richard and Daisy (Young) Saunders, Saunders was raised on North Shore, Pembroke, with his older brother Cyril. Saunders—always known as “Dick”—first became interested in photography as a young boy. He was fascinated by a Mr. Simmons, a black portrait photographer who specialised in taking photos for tourists, and would often follow him around Hamilton. Simmons gave the young Saunders some old equipment for him to play around with.

When he was eight-years-old, his family moved to New Jersey, but they maintained their connections with Bermuda with regular visits back home. The US gave him educational opportunities that were not available in Bermuda.

In high school, Saunders spent long hours, experimenting and developing his skills and taking photos for the school newspaper. Saunders and his family returned to Bermuda after the start of the Second World War.

Saunders initially applied for a photographer’s job with the Trade Development Board (the forerunner of the Department of Tourism) but was rejected as the Board, like many local businesses and organisations at that time, did not employ blacks in professional positions.

But the rejection turned out to be fortuitous. When David Knudsen, an acquaintance and fellow photographer heard his news, he created a job for him at his camera and photo business on Queen Street that would later become The Camera Store on Reid Street. Knudsen and Saunders remained lifelong friends, along with Knudsen’s daughter Betty and son-in-law Crayton Greene, who later managed The Camera Store.

Injustices

During the 1940s, Saunders also worked in photographer Hilton Hill’s studio on Burnaby Street, processing and developing film as well as taking wedding photos and portraits. Hill would later be best man at his wedding. Saunders briefly worked as a police photographer but, disturbed by the social injustices in Bermuda society, became more determined to use his camera to “communicate and educate”.

Although his photos won several prizes at a Government-sponsored exhibition, he was unable to find anyone willing to publish his work. He later claimed that his work made such an impact that he was asked not to enter future exhibitions.

Frustrated by the lack of opportunities in Bermuda, Saunders left for New York in 1945 to take a photography course at Brooklyn College. He also studied humanities and sociology at the New School for Social Research.

On June 29, 1946 in New York, he married Bermudian Emily Wilson, whom he had met in the 1930s. The couple, who had no children, remained married until Saunders’ death in 1987.

Emily, a seamstress, was the muse for Saunders’ first real professional job. She posed in a bikini she made herself at Whale Bay for a glamorous shot commissioned by the Black Star Agency for the July 1947 cover of a new black magazine, Ebony. Saunders was paid around $200 for the shot—a considerable sum in the 1950s.

Freelance

He supported his studies with freelance work, especially in Harlem, with Emily acting as his assistant.

It was through his freelance work that Saunders met Gordon Parks, who would later become one of the top photographers in America, a leading civil rights activist, as well as a film director whose credits include the seminal 1970s movie Shaft. It was a meeting that was to have a profound impact on Saunders’ life and career.

Parks—who would later be Saunders’ sponsor when he became a U.S. citizen and by coincidence had been a member of the Harlem YMCA Camera Club with Hilton Hill in the 1930s—was a staff photographer for Life magazine, at the time one of the world’s most celebrated magazines and famous for its ground-breaking photography.

He helped Saunders land a job working at Lenscraft, the New York lab where leading photographers like Parks, Henri Cartier-Bresson and John Collier took their work to be processed. It gave Saunders a valuable insight into the techniques of some of the world’s top photographers.

It was through Parks that Saunders met Roy Emerson Stryker and got the opportunity to truly establish himself as a serious photographer.

Depression

Stryker, a white American First World War veteran, economist, government official and photographer, had made his mark heading the Information Division of the Farm Security Administration (FSA) during the Great Depression.

He launched the ground-breaking documentary photography movement of the FSA. Through this and other similar projects, Stryker transformed photojournalism with his skills as an inspiring teacher and manager, helping to launch the commercial careers of photographers like Parks, Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans as well as Saunders.

Stryker placed great emphasis on his photographers being well briefed about an assigned area’s people, politics and economy before going out into the field, and encouraged them to look at assignments from a different perspective. He believed that an educated, sensitive photographer would produce images that “would mirror both his understanding and his compassion”. It was an ethic that would become a hallmark of Saunders’ work.

In 1950, Saunders was asked by Stryker to join his team of photographers documenting Pittsburgh’s transition from the ‘Smoky City’ to a modern urban industrial centre for the Pittsburgh Photographic Library at the University of Pittsburgh.

Saunders spent two years living in the poor, mainly black, Hill District taking more than 4,000 black and white photographs of the community before much of it was demolished to make way for the construction of the Civic Arena (now Mellon Arena).

The project resulted in around 18,000 images and was described as “the most complete photographic documentation ever achieved by any American community”. The collection is now housed at the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh.

Humanity

Saunders’ gritty and poignant Pittsburgh images illustrated his ability to bring drama and humanity to a photograph and reflected the sensitivity and integrity that would be a constant throughout his career.

In 1951, the work earned him a prize in Life’s prestigious annual Young Photographers Contest. Saunders soon began receiving regular assignments for leading magazines including the New York Times, Ebony, Look, Fortune, Playboy and Ladies Home Journal. Heturned down the offer of a full-time job on the Times in 1962 because he wanted to focus on photo-essay work rather than daily news photography.

In 1967, a Latin American assignment to document an economic development programme sponsored by the United States Information Agency (USIA) led to the offer of a job as international editor of Topic, a new USIA magazine covering “Africa for Africans”.

Saunders spent the next 19 years based first in Tunisia, and later Washington, DC, travelling on more than 60 assignments for more than 48 African countries, photographing virtually every African head of state and documenting life throughout the continent.

Saunders said travelling to Africa was “like going home” and his work earned him an International Black Photographers Award in1982. The magazine marked his retirement in 1986 by featuring a Saunders image on the cover and an insert of 25 of his best pictures. He was also given the Agency’s Superior Honor Award in 1986.

Inspiration

Just a year later, in August 1987, Saunders died at age 65, in a Washington, DC hospital where he was being treated for diabetes and facing a leg amputation. He died shortly before he was to have received the first-ever Lifetime Achievement Award from the Bermuda Arts Council.

Saunders had been the inspiration for the award, which was established through the efforts of Crayton Greene and Bermudian photographer Graeme Outerbridge, who felt that Saunders’ accomplishments had not been properly recognised by Bermuda.

After his death, Emily Saunders, Topic staff member Rosalie Targonski, and long-time friend and editor Kay Reese, campaigned to make Saunders’ USIA work available to the public. Under the terms of its formation as an Government agency, the USIA was not allowed to distribute any of its information in the United States and Americans were not even allowed to subscribe to Topic.

Eventually in 1991, Harlem Congressman Charles Rangel successfully introduced legislation that lifted the restriction. Saunders’ collection was duly transferred to the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture at the New York Public Library.

Emily subsequently donated much of Saunders' non-USIA archive to the Centre’s Richard Saunders Collection and the Bermuda National Gallery, which held the first major retrospective of Saunders work in Bermuda in 1993, curated by Bermudian photographer Graeme Outerbridge. The Richard Saunders Photography Collection is now part of the Gallery’s permanent collection. Author: Chris Gibbons

| July 22, 1922—Richard Clive Saunders Saunders is born in Bermuda

1930—The Saunders family moves to New Jersey; they return to Bermuda after the start of the Second World War.

1945—Leaves Bermuda for New York; studies photography at Brooklyn College and humanities and sociology at the New School for Social Research.

June 29, 1946—Marries Emily Wilson in New York.

1950-52—Spends two years living and working in Pittsburgh’s Hill District, as part of Roy Stryker’s acclaimed Pittsburgh Photographic Library project.

1951—Wins prize in Life magazine’s Young Photographers’ Contest

February 1952—Saunders’ photo of his wife Emily makes the cover of Ebony magazine.

1967—Joins Topic, a new US Information Agency (USIA) publication covering Africa; he spends the next 19 years travelling to Africa on more than 60 assignments.

1982—Receives International Black Photographers Award

1986—Retires from Topic and given the US Information Agency’s Superior Honor Award.

August 20, 1987—Dies in Washington DC

1987—Posthumously awarded the Bermuda Arts Council’s first Lifetime Achievement Award

1991—Congress changes legislation to allow Saunders’ USIA work to be seen publicly in the US

1993—The Bermuda National Gallery holds a retrospective exhibition of Saunders’ photographs “I thought to myself, that this is a great way to make a living: one hangs out in the fresh air all the time answering to no one.”—Describing how as a child he would following a photographer around Bermuda taking photos of tourists (Black Photographers Annual, Vol. 4, 1980)

“What matters to me are people and their feelings; above all it is the unconquerable dignity of man, of whatever colour, creed or persuasion that must come through in my photographs. Photography is communication: a photograph is nothing unless it is seen and conveys something of life to the viewer.”—Interview with Swiss magazine Camera.

“I could never manipulate my subjects to fit pre-conceived notions or bias. Truth would be changed and become untruth. And I am not concerned about the great technically-executed picture. I want to grasp a precise moment of life, and at that moment one is not concerned with film type or angle. One is interested in sharing an experience.”—‘Exposing The Truth’ by Graeme Outerbridge, RG Magazine,March 1993.

“Many of them [his fellow photographers] and I guess a number of Blacks, felt I was selling out when I went to the (United States Information) Agency. They felt I would get involved in so-called propaganda. Nothing could be further from the truth. My job then, as it is now, was to go into Africa to photograph development stories, stories of people developing their own country. When I go into Africa I look for African development. The pictures I come out with can be published in any consumer magazine because I’m not shooting from a government viewpoint but from a Saunders viewpoint.”—Interview in Black Photographers Annual, Vol. 4, 1980.

“I was on assignment in Kenya and I hired a 21-year-old Kenyan to assist me. I paid him more than the going rate but what I paid him is not important. What is important is that this youth who had never been more than 10 kilometers from his home, had never held a job in his life, went around with me and saw Africans doing things he never dreamed they were doing. He was able to share what I try to share with my camera … He had never in his life seen someone who looks like him, a Kenyan, using sophisticated welding machines and other modern tools. I’m using my camera to allow some fifty to sixty thousand Africans to share this experience.”—Interview in Black Photographers Annual, Vol. 4, 1980.

“If there is such a thing as a Saunders style, it is to emphasise people, especially children. This becomes immediately apparent in any review of his work; personally and professionally, he loves children. He often will go out of his way to include them in his photographs. However he is careful to stay at a distance or put away his camera if he senses he is intruding upon them. As he puts it, ‘If I can bring some hope or a smile on some child’s face, then to me it’s all worthwhile.’ His sensitivity to people is clearly evident in his photographs.”—Topic editor-in-chief Andrew M. Bardagjy on Saunders’ retirement (Topic, 1986)

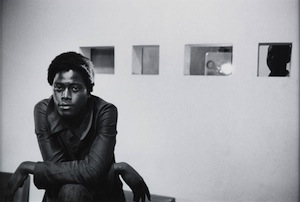

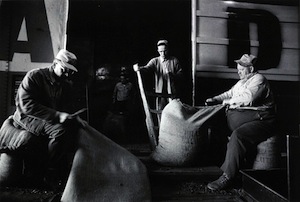

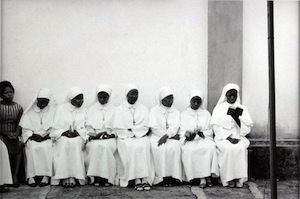

Photographs by Richard Saunders courtesy of the Bermuda National Gallery. Click on image to see larger picture.

You can also view a selection of his images online at Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh  |  | | Senegalese Filmmaker, 1971 | Hershey Factory, Hershey, Pennsylvania, 1974 |  |  | Malcolm X with Elijah Muhammad

and Muslim Dignitaries, 1950s | Celebration of the Mass,

Doula, Cameroon, 1971 |

Further reading

Bermuda National Gallery

Bearing Witness (Exhibition catalogue, Bermuda National Gallery, 2012)

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library

An Illustrated Bio-Bibliography of Black Photographers, 1940-1988 by Deborah Willis-Thomas (1989)

A Century of Black Photographers, 1840-1960 by V.H. Coar (1983)

Exposing The Truth, RG Magazine, March 1993

The Photographers: Richard Saunders – Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh

The Photographers: Roy E. Stryker – Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh

Richard Saunders: Using The Camera To Educate by Joe Crawford (The Black Photographers Annual Vol. 4, Brooklyn, NY, Another View, 1980)

Additional sources

1930 U.S. Census and Bermuda-New York passenger ships’ manifests, 1930s and 1940s

|